It is a sultry evening in August 1974. We are in Everglade Studio, a dingy and down-at-heels recording venue deep in the bowels of a decrepit urban building somewhere in England. Up and coming country-rock singer Skye is cutting some tracks aided by producer Clarke and keyboardist Baron. Clarke has invited black songwriter and singer Matilda along to add a soul vibe to the proceedings. “No real hard black music, nothing street” he tells her, before enquiring “do you have anything churchy for the religious nuts?”

The deeply odious Skye, who has a Confederate flag tattooed on her arm, enquires of Matilda “why has black beauty joined us?” Later she demands, “give us some of that black magic”. The quartet are on a tight timescale and stand to lose every penny they have unless they can come up with the requisite number of songs. As the heat rises conflicts seem set to emerge. What could go wrong?

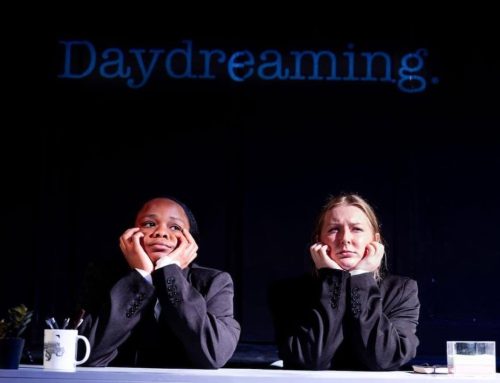

A kind of Pinteresque thriller with songs, In Everglade Studio has a promising first act aided by an enjoyably serpentine performance by Emily Moment as the malign, racist Skye. She really is the absolute limit, although one has to admit the woman can sing. Aveev Isaacson impresses too as the louche, sleezy Baron, even if the character’s accent periodically takes a random excursion from Liverpool to Manchester and back again. Hannah Omisore as Matilda has a perfectly pitched light gospely voice that is a joy to listen to – if only we heard more from her. Nathaniel Brimmer-Beller, who also writes, plays the “brown besuited barnacle” Clarke as an appropriately cynical schemer.

Things veer off in a different direction a third of the way in as a mysterious chemical substance seeps into the studio from the walls, one that sends the quartet high as a kite. Conversations become disjointed. Songs take on new meanings. Power dynamics are inverted. Order turns to hallucinatory chaos. It all becomes very Lord Of the Flies when a gun and a knife are produced.

In Everglade Studio is certainly strong on atmospherics. That disconnected feeling of being sober while surrounded by other people getting very stoned indeed has rarely been so convincing portrayed. The garish brown and orange costumes, and Baron’s impressively hefty sideburns and PE-teacher hair remind us of the 70s’ reputation as the decade taste forgot. The 70s’ other reputation – of a time when casual racist language was still more or less acceptable – is also on show. The songs, lyrics by Brimmer-Beller and music by Isaacson, capture the feel of 70s country-rock without ever approaching pastiche.

But beneath the surface it is difficult to discern what Brimmer-Beller is trying to get at in the piece. Perhaps it is a comment on the sacrifices the creative process demands of artists. Perhaps it is about the ability to lose oneself in music in the same way as some do in drugs. Perhaps it is a just nod to action horror film From Dusk Till Dawn, the vampires here being the characters’ own inner demons unleashed by mind-altering chemicals.

Writer: Nathaniel Brimmer-Beller

Director: Nathaniel Brimmer-Beller and Phoebe Rowell John

More Recent Reviews

Playfight. Soho Theatre.

Writer Julia Grogan’s breathtakingly assured debut play arrives at Soho Theatre following stellar reviews at the Edinburgh Fringe and [...]

All The Happy Things. Soho Theatre.

Naomi Denny’s three-hander comedy-drama All The Happy Things covers familiar themes within a recognisable premise. A grieving protagonist comes [...]

Telly. Bread and Roses Theatre.

The challenge with absurdist comedy is that many people do not find it funny. Laughing at the sheer weirdness [...]