“What do you think? Do I look smart?” is the question Holocaust survivor Yosef Kaufman poses us at the close of The White Factory, Dmitry Glukhovsk’s powerful wartime drama set in the Polish city of Lodz. How we are to judge Yosef and the choices he makes to ensure he survives the Jewish ghetto is one of the central themes of this heart-rending work.

We first meet Yosef (an exceptional Mark Quartley) in 1960’s Brooklyn as he learns of the arrest of Wilhelm Kloppe (James Garnon), erstwhile Nazi commander of the Lodz ghetto and responsible, with others, for the murder of 145,000 people. Kloppe’s detention surfaces long suppressed memories and requires Yosef to navigate the burden of his own participation in wartime events. “Am I a murderer? No, I’m just a witness, an extra”, we hear at one point. But are we to accept this defiant assertion?

The narrative flashes back to 1939. Yosef, then a successful lawyer, lives with fashion-loving wife Rivka (Pearl Chanda), aging father-in-law Ezekiel (Adrian Schiller) and young sons Volf (Leo Franky) and Hermann (Paul-Hector Antoine). The Germans have invaded but Yosef, who is half-Austrian, cannot believe they will be any more antisemitic that his Polish clients. “The Germans aren’t capable of such things” he assures Rivka as rumours of summary deportations and executions reach her ears, and even as the synagogues burn.

Galya Solodovnikova’s set, a sparse white rectangle, fractures into two. A black chasm emerges centre-stage. On one side the delusional and naïve Kaufmans enjoy a family dinner. Yosef tells fairy tales and summons up golems, traditional protectors of imperilled Jewish communities. The boys play with toy trains, a dark foreshadowing of later transports to Auschwitz. One the other side of the stage the methodical Kloppe, and his Gestapo sidekick Herbert Lange (Matthew Spencer) calmy calculate how many victims they can gas in vans per hour and day. The juxtaposition between blind faith and cold fascist evil is stark.

1941 and with the ghetto now sealed off, Jewish elder Rumkowski (Adrian Schiller again and brilliant) sets about making the city so productive that the Nazis will think twice about mass expulsions. “If we give them our sacrifices there will be peace”, he tells the starving inhabitants. A Kaufman family friend is summarily executed for refusing to wear a yellow star. Her blood spatters against the white set and remains there throughout the play; the design motif of white, red and, later, black ashes strewn across the stage floor is viscerally powerful.

Impossible choices follow. To avoid the family’s transportation Yosef concurs with his own father-in-law’s certain demise. Rivka takes a job recycling the pillows of former neighbours into new ones for German families. As she picks the embroidered names of dead friends off pillowcases Yosef urges her to silence; “think logically”, he orders.

Soon, unspeakably, the Nazis demand the ghetto delivers up all children under 10. Yosef elects to save his own family by, baton in hand, rounding up and despatching the offspring of others. “You’re today and I’m tomorrow” is his excuse to the 48 families he has robbed. When Volf and Hermann are arrested, he faces a final choice: sacrifice the entire family to the gas chambers or save himself and his wife.

Quartley tracks Yosef’s journey from self-confident professional to a man almost literally choking under the weight of guilt with magnificent skill. Schiller is superb too as Rumkowski whose own choices are equally impossible and who believes, to the last, that saving one is better than saving none.

Glukhovsk and director Maxim Didenko are both exiles from Putin’s Russia. The relevance of this piece to the invasion of Ukraine is plain to see. Looking the other way, looking after one’s own interests, or succumbing to poisonous narratives when evil unfolds, are temptations that many generations have to face. Yosef’s ultimate task, revealed in a dream-like trial as he gives evidence against Kloppe, is to come to a reckoning with the ghosts of his past: metaphorically speaking to brush away the ashes and wipe the blood off the wall.

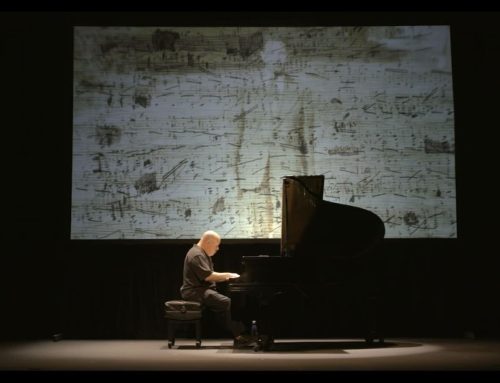

Didenko’s direction sees much of the action videoed live by an onstage cameraman and projected in black and white (although the yellow of the Jewish stars remains) against the back of the stage. It is a technical feat that contributes a feeling of a wartime documentary and communicates that Yosef has nowhere to hide in the decisions he makes. Jewish fairy tales are retold through back projected animations, onto which live performances are imposed through the magic of an onstage green screen. Again, It is tremendously technologically impressive theatre-making, but one wonders here whether the message gets lost in the medium.

Demanding and chilling The White Factory is never less than enthralling. A timely and darkly beautiful piece of work.

Writer: Dmitry Glukhovsky

Director: Maxim Didenko

This review first appeared in The Reviews Hub

More Recent Reviews

Milked. White Bear Theatre.

Written in 2013 and first seen a decade ago in a production at the Soho Theatre, Simon Longman’s slice [...]

Fresh Mountain Air. Drayton Arms Theatre.

Lana Del Rey’s ode to female unity and resilience, God Bless America And All the Beautiful Women In It, [...]

Rodney Black: Who Cares? It’s Working. Lion and Unicorn Theatre.

Rodney Black is a tacky small-time comedian with a venal manager and a taste for nasty misogynism. “I’m a [...]