Thirty years on from the arrival of true democracy in South Africa Paul du Toit’s bioplay The Unlikely Secret Agent, adapted from a book by African National Congress activist Ronnie Kasrils, offers up a timely reminder of the rainbow nation’s dark past. The piece is both a tribute to Kasril’s wife Eleanor and her role in the fight for freedom, and an homage to all those who suffered brutality at the hands of Apartheid security forces. While Du Toit’s narrative is absorbing, even gripping at times, the piece is let down by some oddly atonal efforts at comedy.

It’s 1963 in South Africa, and the nation is teetering on the brink. Political unrest, acts of sabotage, and violence sweep across the land. The vile Apartheid regime, led by Hendrik Verwoerd, ruthlessly crushes any opposition. Amidst the newly enforced State of Emergency, the infamous and brutal Special Branch of the police detains anyone suspected of participating in clandestine activities.

Unhappily married Eleanor (Erika Breytenbach-Marais) works in mum and dad’s Durban bookstore and spends evenings at the ballet, a white South African incarnation of fiddling while Rome burns. A chance encounter with dishy advertising copywriter Ronnie (Wessel Pretorius) sees the two connect. Coffee leads to drinks, a trip to the movies, a burgeoning love affair, and an introduction to Ronnie’s activist circle of friends who belong to Umkhonto we Sizwe, the armed wing of the ANC.

Eleanor thinks all a white “progressive liberal” middle-class woman like her can do to protest is write sarky letters to the press bemoaning her difficulties in travelling by bus with her black maid. Ronnie persuades her otherwise. Soon she is helping to steal dynamite from a building site, sabotaging electricity pylons, and aiding her boyfriend in bombing a Durban post office. “Am I a terrorist?” she asks modestly. “You’re a secret agent” Ronnie assures her.

An audacious attack on Special Branch offices attracts police attention to the couple. Eleanor helps Ronnie escape house arrest but soon finds herself detained at Durban Central Prison. Interrogators Major Steenkamp (Sanda Shandu), Officer Malan (Ntlanhla Kutu), and the odious sexual predator Lt Grobler (De Klerk Oelofse) set out to find out what she knows. “I guarantee I will break you or hang you” Grobler tells her, spitting vitriol. Eleanor feigns mental illness and is transferred to the local mental hospital. Can she find a way to escape before her inquisitors break her?

Du Toit’s narrative time-shifts between Eleanor’s ferocious interrogation, and the events leading up to and following her arrest. It is a structure that mostly works, particularly in recounting the evolving relationship between the two protagonists. Ronnie is a dyed-in-the-wool communist. Initially at least Breytenbach-Marais’s Eleanor is naïve and cocooned in white privilege. One suspects she views her actions as a freedom fighter with a kind of romantic detachment, an extension perhaps of her love for Ronnie. The horrors she subsequently encounters under questioning and her increasingly frantic efforts to escape disabuses her of any notion of privilege. Being “in love with a jew is as bad as being a communist” in the eyes of her captors. “You’re a waste of white skin, do you know that?” Grobler tells her with characteristic venom. Ironically one suspects that white skin is the only thing that is stopping her captors from throwing this convict to her death from the roof of the prison. Hers has become an existential fight for survival.

The narrative flows with momentum and genuine tension. What jars here is Du Toit’s choice to have the male performers switch into a host of other roles, including the many women Eleanor encounters on her journey. Shandu’s Major Steenkamp morphs into the hospital matron replete with nurse’s cap and frumpy attitude. Kutu’s Officer Malan becomes Precious, the put-upon female hospital cleaner and Eleanor’s gossipy middle class female friend Wendy. Oelofse transmutes into a bitchy fellow patient, one of the many alcoholic white women locked up in the hospital.

It is not that these transformations lack dramatic justification, and the four male cast members certainly do their best with what they are given. The problem is the female characters are mostly played for camp laughs. The intention may be to contrast absurdist humour with the stark reality of Eleanor’s situation. Fair enough, but the comic results sometimes feel forced, misjudged, and occasionally almost misogynistic.

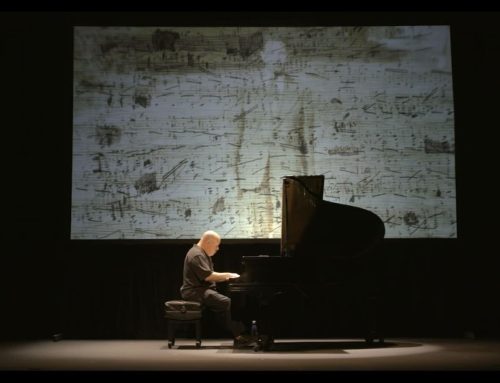

Salene Bekkers’ paired back set effortlessly evokes dingy 60s municipal grime, although back projections of contemporary news footage feel too random to add much to the mix.

Writer and Director: Paul du Toit

More Recent Reviews

Milked. White Bear Theatre.

Written in 2013 and first seen a decade ago in a production at the Soho Theatre, Simon Longman’s slice [...]

Fresh Mountain Air. Drayton Arms Theatre.

Lana Del Rey’s ode to female unity and resilience, God Bless America And All the Beautiful Women In It, [...]

Rodney Black: Who Cares? It’s Working. Lion and Unicorn Theatre.

Rodney Black is a tacky small-time comedian with a venal manager and a taste for nasty misogynism. “I’m a [...]