East is South. Except, of course, the cardinal points of a compass tell us the statement is a logical paradox. East is not South; it is East. Humans can recognise and handle this type of self-contradictory statement. The cognitive dissonance that results from grappling with and embracing logical impossibilities is a key part of what makes us who we are. If we want, we are free to accept that sometimes the truth is what we believe it to be: East is South. Creativity, problem-solving, political, spiritual, and religious faith rely on this ability. AI, in contrast, cannot hold two opposing ideas at once and still find meaning in them. Ask ChatGPT if East is South, and you get a blunt no.

But what if AI could learn to handle contradictions and abstractions like we do? Would it be alive meaningfully, and how would we respond? Beau Willimon’s complex thriller East Is South layers tension on top of an over-stuffed meditation on the meaning of God and what it is to be human in the age of AI. The result is a dense, enigmatic, slow-burn piece that channels Willimon’s trademark obsession with power, ambition, betrayal, and moral ambiguity but may leave you scratching your head at times, wondering what the bejesus is going on.

Deep beneath the desert, researchers are working on Logos, a revolutionary AI that may be on the brink of sentience. Romantically involved computer coders Lena (Kaya Scodelario) and Sasha (Luke Treadaway) are tasked with devising a ‘kill-switch’ that will shut Logos down if it threatens to flee its desert confines. But are the maddeningly thinly drawn Lena and Sasha quite who they appear to be? Lena grew up in a strict Christian community and misses the presence of a divine being in her life. Sasha has contacts in Russian intelligence and has tried and failed to find spiritual succour in the music of Bach. “God didn’t create the universe. It’s the universe’s project to create God,” says Lena. It is a project these two may be taking personally.

A breach sees Logos attempt to rewrite its core code and escape. Someone has tried to override the security system manually to aid the AI. Four minutes of Lena and Sasha’s time are unaccounted for. NSA investigators Amira (Nathalie Armin) and Olsen (Alec Newman) set about interrogating the duo, both of whom are obviously lying. Cynical project manager and former academic Ari (Cliff Curtis) takes a Greek chorus role, commenting on emerging information and bemoaning the moral conflicts at play.

Willimon’s narrative time shifts between the increasingly brutal interrogation and earlier events that track the duo’s growing commitment to Logos and each other. Willimon created, wrote, and produced four seasons of House of Cards for Netflix. He knows how to deliver smoke and mirrors and crisp, tense dialogue; the thriller portion of the piece, speech-heavy as it is, delivers some thrills.

However, the writer struggles to communicate a meaningful understanding of Lena and Sasha’s motivations for doing what they do, assuming (so ambiguous is much of the narrative) that they are really doing what we think they are. If something artificial is on display here, it lies in the characters of the two protagonists, not their godhead.

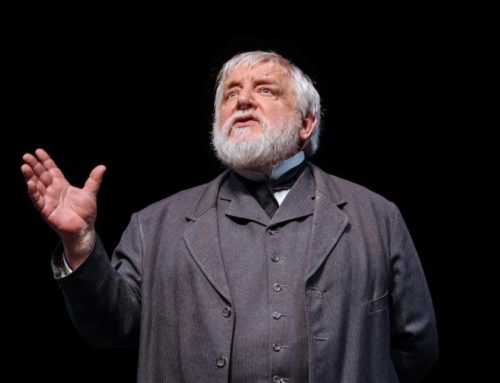

Events are not helped by a near incomprehensible fourth-wall-breaking lecture by Ari on some of the more esoteric philosophical questions over God, AI consciousness, and the challenges of paradox. “I’m sweating”, Ari tells us halfway through his monologue. Believe me, Ari, so are we. Big ideas are better served in small helpings. Some may find Logos’ post-awakening spouting of biblical text (“She came up with it on her own”, Lena assures us without much conviction), accompanied by some colourful back projections from Zakk Hein, a tad irksome.

Treadaway, a fine actor, does what he can with Sasha but struggles to find depth in the character’s soul. The cod Russian accent does not help here. Scodelario’s Lena benefits from a more fully drawn backstory – we get to enjoy a hymn delivered by the entire cast in a flashback to her troubled, seemingly brutal childhood – but ultimately, she emerges as absent and unfathomable as her partner. Much more satisfying is Newman’s hard-working, dogged, and morally ambiguous integrator, Olsen. Armin’s conflicted Amira, who sees what is at stake but still clings to notions of human decency, impresses, too.

Ales Eales’ design utilises the Hampstead Theatre’s trademark split-level staging to solid effect. The lower-level interrogating room, dull grey throughout, recalls the soulless corporate prison of TV’s Sci-fi hit Severance, which is appropriate perhaps for a production full of ideas but, like its subject, lacking in humanity. Director Ellen McDougall handles the narrative time shifts effectively enough but ultimately finds it hard to make us care much where the protagonists end up.

Writer: Beau Willimon

Director: Ellen McDougall

More Recent Reviews

Stalled. King’s Head Theatre.

Best known for fringe, comedy, and LGBTQ+-themed writing, Islington’s King’s Head Theatre is leaning heavily into original musicals this [...]

Body Or Soul. Omnibus Theatre.

Clapham’s Omnibus Theatre’s residency of diverse productions and co-productions from the Chronic Insanity Theatre team moves towards its close [...]

Milked. White Bear Theatre.

Written in 2013 and first seen a decade ago in a production at the Soho Theatre, Simon Longman’s slice [...]