After nearly four decades in show business, Tony Award-winning playwright and Oscar nominee screenwriter John Logan probably knows as much as anyone about the power games that take place between and directors and actors. “Moments of grace emerge from horrible humiliations” is how one of the characters in Double Feature, Logan’s new play at London’s Hampstead Theatre, sums up the relationship. Ten years in the writing, Double Feature interweaves two different tales from the golden age of Hollywood to elucidate the point.

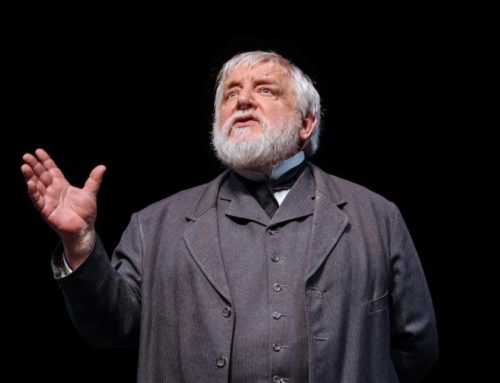

It is 1967 and we are mid-way through the filming of low-budget British horror movie Witchfinder General. Aging film star Vicent Price (Jonathan Hyde), furious at the on-set humiliation he believes he is suffering at the hands of neophyte director Michael Reeves (Rowan Polonski) is threatening to walk. “Who do I have to fuck to get off this picture?” the star says, necking whiskey in the living room of Reeves’ rented English country cottage.

Anxious to stop the “smirking fake of a jobbing hack actor” from leaving the production in the lurch, Reeves enquires what Price’s price is for staying. “I expect you to beg”, star tells director as he derides his “delusions of Truffaut”. “On your knees, they’re between your cock and your feet” he adds helpfully. Reeves, a depressive scared “of artistic compromise, dogs, horses and England” (and himself) has his work cut out. Mismatched power dynamics are rarely as brutal as this.

Cut to 1964 and Alfred Hitchcock’s (Ian McNeice) fake English cottage on the Hollywood backlot of Marnie, not a horror movie but certainly a movie packed with horrors. Marnie’s leading actress Tippi Hedren (a sublime Joanna Vanderham) has been summoned to a late evening rehearsal of the movie’s infamous rape scene. Hedren want to talk about her character’s motivation and wonders why on earth the film’s protagonist would end the movie staying with her abuser.

Hitchcock’s motivation for the meeting is a good deal baser. “A lady should always look like she’s just swallowed cum,” he says grotesquely, just to make crystal clear who is in charge here. My movies are either “kiss kiss or kill kill” Hitchcock tells Hedren. Then with awful foreshadowing of the horrors of Harvey Weinstein and his ilk, he says “we all have to suffer to earn our kiss”. Marnie’s story and backstory converge, rendering the cruelty that goes into its production palpable and visceral.

Double Feature is about the painful but ultimately creative subversion of the power relationships in each situation, in one case through a show of strength and in the other through a demonstration of vulnerability. It has much to say about the contrast between film and theatre, the purpose of art, and the different ways in which creatives conceive of character and narrative. Logan’s point here is that the process of artistic creation is almost inevitably painful and almost always requires some form of negotiation between actor and director, each of whom holds different amounts of power. It is a theme Jack Thorne explores in the National Theatre’s superb The Motive and The Cue.

Logan’s ability to interweave the two stories is technically remarkable. Reeves quotes a favourite movie line drawn from Hitchcock’s Vertigo. Price discusses the finer points of Psycho. Words and ideas pass from one narrative to the other in a fashion that is almost musical, revealing and exploring aspects of both relationships that might otherwise have been concealed. Logan’s writing is brilliantly economic in the way it reveals character: “Less voice, no butter, do less” Reeves tells Price at one point. “How much less?” Price responds. “Nothing” says Reeves. “Yes, but how much nothing?” insists the bewildered star.

Jonathan Kent’s direction is spot on. At one point the four characters share the same kitchen table, Reeves and Price eating spaghetti while Hitchcock and Hedren enjoy oysters and consommé. It is a conceit that might feel clumsy but is perfectly pulled off, aided by subtle lighting changes from Hugh Vanstone. Anthony Ward’s evocative set is packed with cinematic reference points.

McNeice’s sinister and bullying Hitchcock chunks his dialogue into gulps of two or three words. This is the feel of a man struggling for breath under the weight of his own humungous sense of self-importance. Vanderham captures Hedren’s ability to evince both emotional absence and deep-seated aggression with the flick of an eyebrow. Polonski could do with speaking a little louder (it is a long way from the stage to the back of Hampstead’s stalls) but his vulnerability as Reeves is impressive. Hyde channels Price’s arch campness with utter charm.

All in all, something of a theatrical tour-de-force.

Writer: John Logan

Director: Jonathan Kent

More Recent Reviews

The Sea Horse. Golden Goose Theatre.

The Sea Horse, Edward J Moore’s grim slice of mid-century realism, debuted to solid reviews off-Broadway in 1974. Since [...]

Garry Starr: Classic Penguins. Arts Theatre.

Emperor penguins’ shortish treks between sea and nesting sites are about as peripatetic as your average Thameslink commuter. Garry [...]

When the Clarion Came to Call. Cockpit Theatre.

When, upon entering an auditorium, you are told, ‘Take as many pictures as you like, but mind the ceramics,’ [...]