China’s government is currently engaged in a battle against what it labels separatism, terrorism, and extremism in the nation’s far-northwest autonomous region of Xinjiang. Estimates suggest that between one and three million of the region’s population of Uyghur Muslims have been imprisoned and brutalised in a vast, secretive network of purpose-built detention camps that, China insists, are voluntary schools.

The programme’s aim is to eradicate the ‘thought virus’ of local customs and religious beliefs, implanting in their place the secular, communist, values and attitudes of the majority Han culture. Credible evidence from multiple sources suggests torture, rape, and other human rights abuses are apparent throughout the detention system, including the forced sterilisation of female Uyghurs.

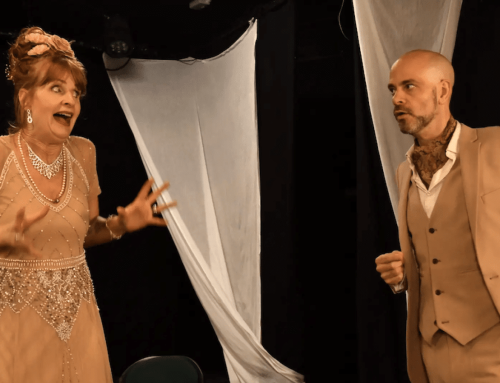

Loosely based on the real-life story of the once high-profile Uyghur dancer and male model Merdan Ghappar, Peter Barnett’s Thought Virus is an authentic, thought-provoking, and often moving attempt at bringing a human face to the plight of an entire people.

It is 2018. Uyghur teenager Erkin (Mert Degirmendereli) has been offered a modelling contract in distant Beijing. Dad Alim (George Savvides) would prefer he stays put in Xinjiang; “I can put in a word for you at the factory” he says optimistically. Mum Reyhan (Baris Celiloglu) worries about the racism her son will face in the East, “better tell them you are European and keep the Muslim thing to yourself” she cautions. Neighbours Aynur (Lena Lapres) and Yusup (Guney Akis) bridle against random police inspections and fret about family and friends who have simply vanished.

Erkin’s initial success in Beijing brings money, fame, a plush apartment (having a Muslim name means he cannot register property in his own name) and drinks with the editor of Chinese Vogue. But a problem arises in the form of Erkin’s politically active uncle who, exiled in the Netherlands, is organising mass demonstrations against authoritarian oppression.

Arrested and imprisoned for a minor offence Erkin soon learns it does not pay to have noisy relatives abroad. The teen is about to face, head-on, the stark reality of so-called rehabilitation. Fellow inmate Shahram (an impressively stoic Terry Burns) and the boy’s faith offer little protection against systemic cruelty. Meanwhile back in Xinjiang a sinister and cunning government Homestayer (Steve Hanzheng Wu on good form) moves into the family’s modest residence. His aim is to educate Alim and Aynur on how to be proper Chinese parents and monitor communication’s with Erkin’s wayward uncle.

Barnett’s narrative is told out of chronological order, jumping back and forth between Xinjiang, Beijing, and life in detention. The time-shifts add pace, as does some snappy direction from Jason Moore, but aside from Burns’ turn as the unyielding inmate Sharam there is little by way of depth to these characters. Their suffering, laid out with precision though it is, feels somehow clinically detached from the personalities on stage. One feels deeply for the predicament of a people, if not always these particular people.

Merdan Ghappar has not been heard of since 2020 and in all probability remains imprisoned. Barnett’s key success in Thought Virus is ensuring that Ghappar’s name is not forgotten and that the suffering of his compatriots remains firmly on our agenda.

Writer: Peter Barnett

Director: Jason Moore

More Recent Reviews

Playfight. Soho Theatre.

Writer Julia Grogan’s breathtakingly assured debut play arrives at Soho Theatre following stellar reviews at the Edinburgh Fringe and [...]

All The Happy Things. Soho Theatre.

Naomi Denny’s three-hander comedy-drama All The Happy Things covers familiar themes within a recognisable premise. A grieving protagonist comes [...]

Telly. Bread and Roses Theatre.

The challenge with absurdist comedy is that many people do not find it funny. Laughing at the sheer weirdness [...]