For all its charm, Ambreen Razia’s drama about three generations of women in a British Asian family never quite takes off.

30 June 2022 Press Night

Productions that feature working class families from minority backgrounds are underrepresented in modern British writing (the Kiln’s Black Love, the Bush’s House of Ife and Hampstead’s fantastic Lotus Beauty being honourable recent exceptions to the rule).

So, it is great to see the gifted young actor Ambreen Razia get a showing for her commendable-if-flawed, female four-hander Favour, ably directed at the Bush by Róisín McBrinn and Sophie Dillon Moniram.

Based on the evidence of this show, Razia has as much potential as a writer and she does skills as an actor, although I suspect there is better to come from her than the mixed-bag that is Favour.

When the play works best is in its depiction of the toll taken on generations of Asian women by the need to fit in to a culture that is simultaneously alien in its values, and attractive in its apparent freedoms. It also has something to say about how the conservatism of some Asian cultures still inhibits women from living the kind of lives they want.

First generation Pakistani immigrant Noor lives in a spick and span council house in Ilford with her artistically gifted 15-year-old grand-daughter, Leila.

In the awkward absence of Leila’s mother Alina, imprisoned apparently for drunk-driving, Noor has done a sterling job bringing up the hijab-clad teen to be a respectable, hard-working, if anxiety-prone member of the local Muslim community.

Things are about to change, however.

There a ‘Welcome Home’ poster on the wall to celebrate Alina’s impeding release. It is fair to say that Leila is keener to see her mother than Noor is to see her wayward daughter.

Recovering alcoholic Alina, who could never live up to the motherhood standard set by her supposedly perfect elder sister, comes out of prison with her own agenda for Leila’s future.

Aided by a prison sojourn spent with her Buddhist cell-mate, the newly-confident Alina has connected with her chakras, discovered her inner animal spirit, and will not take no for an answer.

But has anyone actually asked Leila what she wants?

The unfolding of events is greatly aided by the sporadic appearance of snobby neighbour Auntie Fozia who, aside from adding some comic light and shade to proceedings, acts as a catalyst for the emergence of some unwelcome truths and hidden secrets. At the end of the play nothing will be the same for the women concerned.

Razia’s storylines provide a solid-enough springboard for some interesting revelations. But the ending is weak and it is best to avoid interrogating the narrative arc too closely, as quite a few of the character choices are hard to swallow.

Pretty much as soon as she gets out of the nick Alina skips probation service appointments, exhausts mum’s credit at the local store, and goes out on a vodka-fuelled, shop-lifting spree. Fair enough as a way of demonstrating the ex-con’s character, but it is all quite at odds with her supposed motivation to reclaim her daughter.

More unlikely still is Leila and Noor’s apparent insouciance towards Alina’s reversion to her old addictive behaviour. I am also dubious about whether the probation service would ignore all those missed appointments, or whether social service would not have something to say about Leila’s uprooting to a shared bedsit in Kent. I might be picky, but the willing suspension of disbelief in a theatrical audience requires a writer to think these things through.

There is also an odd dream-like scene in the middle part of the play that struggles to work. The Ilford living rooms mysteriously transforms magically into a nail salon, beauty lights emerge from the walls, and a refreshing fruit mocktail emerges from a nook in the wall. All this, as Alina alternates between begging, imploring, and threatening a daughter who is reluctant to move home. It is all a little out of kilter.

Avita Jay gets the addict’s characteristically maniacal twists and turns just right in her portrayal of Alina, but there is not a huge amount of character development going on.

Ashna Rabheru seems older than her supposedly teen character, but otherwise does stalwart work showing a Leila growing in confidence by the minute. Renu Brindle is also great is the buttoned up Noor, who cannot quite ever tell her daughter she loves her.

Rina Fatania offers the standout performance as Fozia. The actor has a rising guttural tone to her voice that sounds like a cross between tiger’s roar and the oncoming arrival of a steam train. I could have listened to her all evening.

I look forward to seeing more, and better, from writer Razia. But in the meantime this is well worth a look.

Writer Ambreen Razia

Co-Director Róisín McBrinn

Co-Director Sophie Dillon Moniram

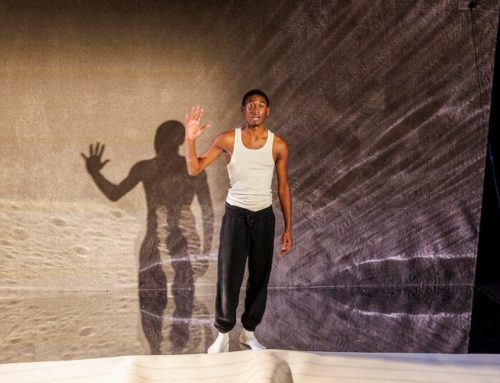

Ashna Rabheru Leila.

Avita Jay Aleena

Rina Fatania Fozia

Renu Brindle Noor

Duration: 95 minutes, No Interval.

Full Disclosure: I paid full box-office price for the ticket.

More Recent Reviews

Playfight. Soho Theatre.

Writer Julia Grogan’s breathtakingly assured debut play arrives at Soho Theatre following stellar reviews at the Edinburgh Fringe and [...]

All The Happy Things. Soho Theatre.

Naomi Denny’s three-hander comedy-drama All The Happy Things covers familiar themes within a recognisable premise. A grieving protagonist comes [...]

Telly. Bread and Roses Theatre.

The challenge with absurdist comedy is that many people do not find it funny. Laughing at the sheer weirdness [...]