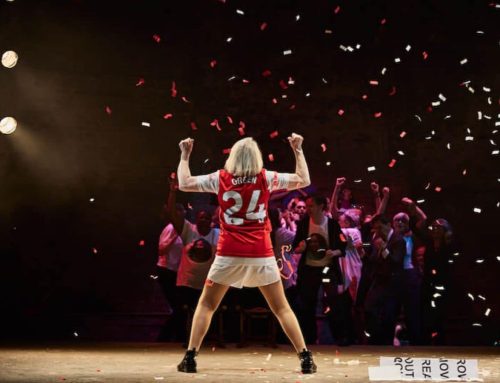

Beth Steel’s exploration of secrets and lies in three generations of a Northern working-class family is made magnificent by Anne-Marie Duff.

18 May 2022

“The dead are a heavy burden” intones Alistair, one of the characters in Beth Steel’s complex, multi-layered, and highly ambitious new play, The House of Shades.

At its core, the play is about how, long after their demise, the ghosts of things long gone lay a heavy load on the people left behind.

At one level the story explores how the loss of parents, partners, and most compellingly a dead child, place a sometimes impossible burden on the living. At another level it is about how the passing of an entire working class culture, at the hands of Thatcherism and globalisation, impacted on the generations left to live on.

I am also tempted to think that the writer feels the weight of a lost working class theatrical tradition pressing down on her, because there is an awful lot of retro homage to the tropes of kitchen sink realism squeezed into the play. Abortion, class, gender, adultery, plenty of shouting, it all gets a look in. There is also, in a gloriously knowing reference by Set Designer Anna Fleischle, a grimy kitchen sink, packed with dirty dishes and the drip-drip-drip of a leaky tap.

It takes a writer of quality to make these three strands – the personal, the political, and the theatrical tradition – merge together into a cogent piece of work. Broadly-speaking Beth Steele pulls it off, aided by some snappy direction from Blanche McIntyre.

The story starts in 1965, with a local neighbour-cum-narrator ‘laying-out’ the body of Constance Webster’s brutal and unlamented father, a man she can never forgive for stopping her from attending grammar school.

Constance, superbly played by Anne-Marie Duff, quotes Bette Davis pithiest movie-lines, so you can guess she is probably going to be a nasty, if charismatic, piece of work.

Quite how toxic she can be is not revealed until the later stages of the play, and it is a testament to Duff’s powerhouse performance (and fantastic singing voice) that we never lose compassion or understanding for a deeply unsympathetic character.

Trapped in a mistaken marriage with the dull but worthy shop-steward Alastair, Constance rails against lost opportunities, finding comfort in the vodka bottle and in the ballads that might, in another life, have made her a singer. Almost her only consolidation is the knowledge she will soon be free from the ‘prison of motherhood’, now that her twins, budding tory-boy Jack, and Left-wing firebrand Agnes, are grown up, and only teenage Laura remains.

When Laura gets pregnant, Constance is determined not to let the pregnancy proceed. But it is two years before the Abortion Act and the local back-street abortionist is none too keen to help the Webster family out. What happens next forms the central story arc and will haunt the family for two generations to come.

We see the family again, in various combinations of life and death, at the end of old-Labour Britain in 1979, at the height of Thatcherism in 1985, on the cusp of Blair’s New Labour in 1996, and shortly after Johnson’s Brexit-driven 2019 election.

All this might all sound like rather a gloomy and ‘grim-up-north’ moan-fest, and there is no question that Steel has a political agenda she wants to communicate. But she is a canny writer who knows how to deliver light and shade, so even at its most polemical it remains engaging.

Steel also knows when to take risks.

As a way of coming to terms with the burden of the past therapists often suggest engaging in metaphorical conversations with those we have lost. In The House of Shades, the writer imagines some of these conversations as real – Jack converses with his dead father; Alastair casually chats with a long-dead political hero; a dying Constance faces a long dead lover, her younger self, and the haunting vengeful figure of the daughter she lost decades earlier. It is an effective technique that adds a welcome level of urgency to a narrative that occasionally loses pace.

Less effective, dramatically-speaking, are the mournful ballads that Constance sings under a spotlight at the front of her kitchen. Wonderful to listen to, yes, but theatrically redundant.

I was not entirely convinced the by ending, in particular Jack’s final act of score-settling with the memory of his sister. But overall, a highly watchable piece of work made memorable by an award-worth central performance.

CAST & CREATIVES

Writer Beth Steel

Director Blanche McIntyre

Set Designer Anna Fleischle

Cast

Teenage Jack Gus Barry

Constance Anne-Marie Duff

Neighbour Beatie Edney

Agnes Kelly Gough

Jack Michael Grady-Hall

Helen Emily Lloyd-Saini

Edith Carol Macready

Alistair Stuart McQuarrie

Aneurin Bevan Mark Meadows

Eddie Daniel Millar

Teenage Agnes Issie Riley

Laura Emma Shipp

Duration: 2 hours 45 minutes. One interval.

Full Disclosure: I paid full box-office price for the ticket.

More Recent Reviews

Playfight. Soho Theatre.

Writer Julia Grogan’s breathtakingly assured debut play arrives at Soho Theatre following stellar reviews at the Edinburgh Fringe and [...]

All The Happy Things. Soho Theatre.

Naomi Denny’s three-hander comedy-drama All The Happy Things covers familiar themes within a recognisable premise. A grieving protagonist comes [...]

Telly. Bread and Roses Theatre.

The challenge with absurdist comedy is that many people do not find it funny. Laughing at the sheer weirdness [...]