The Clinic, Dipo Baruwa-Etti’s much anticipated new dark comedy drama at the Almeida Theatre, has a favourable enough central conceit. Place a grieving, suicidal black rights activist, together with her infant child, into a wealthy, smug, but fundamentally troubled British Nigerian family and watch the sparks fly. What could go wrong? Alas, quite a lot. It begins strongly, but despite some pleasingly caustic comic exchanges and first class performances from the female leads, it ends up feeling disappointingly dry.

It begins favourably enough. Tory-voting psychotherapist Segun (Maynard Eziashi) lives the good life with women’s shelter volunteer wife Tiwa (Donna Berlin). The couple’s luxury London townhouse, expensive tastes in wine, and medical school for grown-up daughter Ore (Gloria Obianyo) are all funded by Segun’s string of bestselling memoirs. Even police detective son Bayo (Simon Manyonda) has the improbable good fortune of marrying disillusioned local Labour MP Amina (Mercy Ojelade). With so much potential to do good at their disposal, little wonder that Tiwa jokingly refers to her family as ‘The Clinic’. All they lack is a suitable recipient for their largesse.

Set throughout in the kind of cool and contemporary modern kitchen beloved of upwardly mobile Islington types, the action kicks off robustly enough. It is family gathering for Segun’s sixtieth. There is a cake burning in the oven, which could be causal happenstance but is probably ominous foreshadowing of some inflammatory events ahead. From the chaotic bickering and tetchy needling, we make out a family whose ostensibly functional surface dynamic betrays hidden turmoil. Relationships are ready to spiral off into open antagonism at any moment, especially between the chain-smoking, wine-quaffing Doctor Ore and her buttoned up brother Bayo and his wife. These first few scenes, cleverly intercut with vignettes from Ore’s workplace, are an object lesson in how to establish place, tone, and character. If only the rest was half as good, or funny.

Enter working class radical Wunmi (Toyin Ayedun-Alase) and her infant son August. Doctor Ore failed to save Wunmi’s much-loved husband Jo from a preventable death, leaving the grief-stricken young mum planning to kill herself with a morphine overdose. What better sanctuary for her to regain mental health, thinks Ore, than in Segun and Tiwa’s expansive and comfortable family home.

Savvy guest Wunmi becomes increasingly drawn to the attractions of the couple’s commodious lifestyle, allegorically embodied in her burgeoning addiction to Tiwa’s special recipe of magical tea. She soon finds herself wearing Ore’s clothes and cooking her signature fried plantains for family dinners. But can she really reconcile her political beliefs with her new-found comfort? And what unpredictable consequences will her presence have on her hosts and their offspring?

Fire is the central recurring motif in The Clinic. Tiwa references it early on, “there are flames in your eyes, telling me you’re going to be a wildfire. Let it burn!” she says, cajoling a suspicious and hostile Wunmi to set aside her activism and become more like the family. No surprise that Segun’s new self-help book is entitled Rising From The Flames. “Not everyone can be saved” he laments, “sometimes you just have to stand back and watch them burn,” which is pretty much the audience’s role here.

But it is Wunmi who adopts “Let it burn!” as a kind of battle cry, guiding her response to the neediness, absence of communitarian empathy, and insufficient political consciousness she imagines in her family of hosts. To rub the point in, director Monique Touko engineers flickering theatre lights and the sharp crack of sparking electricity whenever a particularly combustible encounter occurs between activist and family member. The stagecraft feels unnecessarily portentous in a narrative that is already jam-packed with the complex metaphor that characterises Baruwa-Etti’s style. Audiences really do not need this kind of handholding.

The Clinic never lives up to the acid promise of its first 30 minutes. It smoulders, splutters into life mid-way in an intriguing scene between Wunmi and Amina, but rarely, dramatically speaking at least, catches fire. The scenes with the whole family sparking off each other are the most satisfying, but even the cleverly camouflaged twist-in-the-tail fails to fully ignite. Partly this is because it feels the characters Baruwa-Etti is most interested in, or engaged with, are those amenable to the kind of political passage he seems to favour. Fair enough from the perspective of polemic, but it leaves the remaining personalities thin. Without much to do, the men, particularly Bayo, feel underwritten and cipherlike.

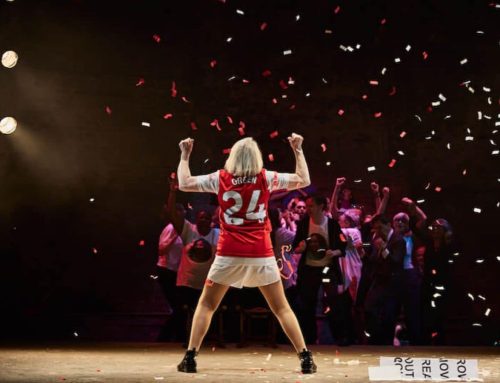

Narrative flaws aside, there are some quality performances to enjoy. Obianyo brings an admirable dose of weary and bitter cynicism to her performance as increasingly disheartened daughter Ore. Berlin plays matriarch Tiwa with the all the force and unpredictability of an Autumn gale. A terrifically charismatic Ayedun-Alase brings out Wunmi’s rage and grief with fierce effect, but she struggles to create much compassion for a character who is a little too comfortable with the status quo. Indeed, setting aside sexual attraction and misdirected maternal urges, it is hard to believe that Tiwa and Segun would put up with the activist’s presence in their home for long.

The Clinic poses some interesting questions about the costs that activism incurs on the politically involved, the role of family in British black culture, and about the solidarity that the wealthy and successful owe to less privileged members of a systemically disadvantaged community. Though never less than watchable, and with some laugh-out-loud comic moments, it sometimes feels like the writer is not giving his characters the headway they deserve.

12 September 2022

Duration: 2 hours 20 minutes. One interval.

This Review First Appeared in The Reviews Hub

Writer Dipo Baruwa-Etti

Director Monique Touko

Cast

Toyin Ayedun-Alase

Donna Berlin

Maynard Eziashi

Simon Manyonda

Gloria Obianyo

Mercy Ojelade

More Recent Reviews

Playfight. Soho Theatre.

Writer Julia Grogan’s breathtakingly assured debut play arrives at Soho Theatre following stellar reviews at the Edinburgh Fringe and [...]

All The Happy Things. Soho Theatre.

Naomi Denny’s three-hander comedy-drama All The Happy Things covers familiar themes within a recognisable premise. A grieving protagonist comes [...]

Telly. Bread and Roses Theatre.

The challenge with absurdist comedy is that many people do not find it funny. Laughing at the sheer weirdness [...]