Before the ‘angry young men’ of the 1950s, so we are often told, British theatre was dominated by well-crafted drawing-room comedies, detached from the struggles of ordinary people and as often as not written by closeted, wry, witty gay men. The history lesson is a tad simplistic. But there is no doubting the impact Arnold Wesker’s 1959 ensemble drama Roots and John Osborne’s 1956 behemoth of a play Look Back In Anger, among others, had on contemporary audiences. Intense, raw, socially conscious narratives, peopled by working and lower-middle characters bemoaning disillusioned alienation, social injustice, class struggles, and postwar angst landed with the impact of a theatrical whirlwind. In the Netflix age, the themes can feel a little passé.

The Almeida’s Angry and Young season sees the two ageing kitchen sink dramas running alongside each other in repertory for 11 weeks with a shared cast, programme and set. The mirror they held up to 1950s society is now consciously (and not always successfully) angled towards 2024. Be warned, the combined running time of both shows is four-and-a-half hours which makes seeing them on the same day something of a task.

On paper, at least Wesker’s tale of a working-class woman finding her voice offers the perfect juxtaposition to Look Back In Anger’s (reviewed separately) toxic masculinity and loathsome domestic abuse. Both pieces are, at least at one level, about their characters’ persistent inability to communicate. Opinions will vary as to whether pairing the two in repertory delivers insight in addition to balance.

Diyan Zora production of Roots is, if nothing else, hugely enjoyable, aided by two blisteringly good performances from Morfydd Clark (currently to be seen in Amazon Prime’s Lord of The Rings spin-off) as the young, idealistic, lovestruck Beatie, and Sophie Stanton as her practical but sceptical mother Mrs Bryant.

“Why do fools fall in love?” croons farmer’s wife Jenny (Eliot Salt) at the outset of the piece. Beatie would do well to ponder the question. Ronnie, Beatie’s boyfriend of three years, is an intellectual type with a Shavian determination to educate his girl in the finer things of life. Ronnie chooses Beatie’s dresses and sets her to a hobby of abstract gouache painting; at which pursuit she pointed fails to demonstrate talent.

Beatie, smitten and overawed, wants to pass on her newfound knowledge to her stick-in-the-mud rural family. Diyan Zora has Beatie climb a chair and stand under a single spotlight when she parrots Ronnie’s views to her bewildered folks, channelling the man’s bombastic intellectual grandstanding as if he is some kind of cosmically gifted star turn. “I don’t quote all the time, I just tell what Ronnie says,” Beatie tells us, which sums things up neatly.

Ronnie (only ever an offstage presence) plans his first-ever visit to his girlfriend’s parents. “I don’t want Ronnie to think I come from a small-minded family” worries Beatie, a fair concern when her people’s main topics of bickering involve whist drives, pig breeding, marital dissatisfactions, local lottery funds, and seemingly inappropriate sexual solicitations by a farm hand. This is a “mighty clan” whose main preoccupation is the state of their guts – filling them or moaning about the discomfort arising from filling them.

Conflict ensues when Beatie’s family prove resistant to her educational zeal. “Don’t come pushing ideas at us” says Jenny’s country bumpkin husband Jimmy (Michael Abubakar). Defensive mum, whose days are marked by counting the arrival and departure of village buses (a reminder of those halcyon days in the 1950s when rural villages had bus services) proves the hardest for Beatie to inspire. “Words are bridges,” says the girl. “Words ain’t supposed to be a laxative” retorts Mum, by which she means they are not here to provide anyone with any comfort. A furious Beatie tells Mum “You have no majesty”.

Beatie’s journey involves finding a voice that is authentically her own, one that is not just a parody of Ronnie’s eclectic musings. Wesker’s set-up is an awfully slow burn that takes most of acts one and two: waiting for Ronnie to turn up sometimes feels akin to waiting for Godot, albeit with the smell of baking and the warmth of a family kitchen by way of comfort.

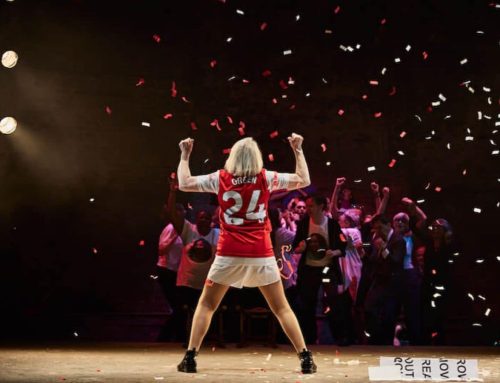

When Beatie finally finds her voice, it comes almost as a surprise. One wonders whether writer Wesker loses patience with the absent Ronnie, so determined is he to make his point through his protagonist’s act three soliloquising. “I’ll get you bastards thinking if it’s the last thing I do” Beatie shouts at her family, but one suspects it is Wesker talking to (or at) us.

Roots’ political messaging might prove a tad heavy-handed for Gen Z audiences, but there is humour, imagination and compassion in Wesker’s writing and Zora’s production evinces a refreshing disdain for easy cynicism.

Writer: Arnold Wesker

Director: Diyan Zora

More Recent Reviews

Playfight. Soho Theatre.

Writer Julia Grogan’s breathtakingly assured debut play arrives at Soho Theatre following stellar reviews at the Edinburgh Fringe and [...]

All The Happy Things. Soho Theatre.

Naomi Denny’s three-hander comedy-drama All The Happy Things covers familiar themes within a recognisable premise. A grieving protagonist comes [...]

Telly. Bread and Roses Theatre.

The challenge with absurdist comedy is that many people do not find it funny. Laughing at the sheer weirdness [...]