Accusations of misogyny dog John Osborne’s 1956 masterpiece Look Back In Anger. The work bleeds toxic male despair. To a modern audience, it can feel like an extended rant from an Andrew Tate prototype, so be warned. One critic has even described it as a kind of revenge porn, written in bitter response to the collapse of the writer’s marriage. Perhaps that explains why the piece, arguably the most significant British drama of the twentieth century, sees vanishingly rare major London revivals.

The Almeida’s Angry and Young repertory season counterpoints Osborne’s magnum opus (perhaps curated would be a better description) with Arnold Wesker’s highly regarded Roots. The two kitchen sink dramas run alongside each other in repertory for 11 weeks with a shared cast, programme, and set. Roots (reviewed separately) oozes hope for the future and has a female protagonist at its core. Much of its momentum emerges from a fraught mother-daughter relationship. Look Back In Anger, in contrast, leaches hopeless masculine entitlement. The juxtaposition of the two pieces is sharp but whether either one shines additional light on the other is open for debate.

Billy Howle’s Jimmy Porter gives us vulnerability amidst the bitter disaffection. Perhaps there is a suggestion in the performance that clinical depression drives much of man’s hand-wringing and hateful fury. The character certainly looks like he is at the end of his tether, evincing a kind of learnt helplessness. This is a lab rat who has long since given up trying to get the reward. Howle’s Jimmy fidgets, his tongue pops in and out of his mouth like a jack-in-the-box, boiling volatility threatens to spiral from fury into outright violence. “Stupid bitch” he says of a letter writer. “She hasn’t had a thought for years,” he says of his wife of three years, Alison (a slow-burning turn of immense power from Ella Torchia). That is just in the first five minutes.

It is just possible to empathise with the repulsive Jimmy. Traumatized by the slow death of his father he is loyal to a fault, at pains to see the mother of his oldest friend gets the funeral send-off she deserves. He is oddly untroubled by the physical attentions flatmate Cliff (Iwan Davies) bestows on Alison, which in Atri Banerjee’s production are more those of brother and sister than the stylised sexual flirtations of previous outings.

Howle’s Jimmy is also fiendishly clever, intellectually courageous and very, very funny. And to be fair to the man he is not just misogynistic; “he hates all of us” as Alison tells us. Most of all he hates himself. Other people’s perceived faults are so manifestly projections of the character’s self-loathing that one is constantly surprised a man as bright as Jimmy does not see that.

The question hanging over past productions of Look Back In Anger is why is Jimmy so angry? Odd really, because if anyone in the piece has a right to feel angry it is the woman. Alison’s passivity in the face of unrelenting aggression remains deeply shocking. Of course, seventy years on women (and men) still allow themselves to remain locked into abusive domestic relationships. Ella Torchia’s Alison, gulping down tears and chain-smoking, offers up the only reason for staying she can: she loves him. Familiar, but somehow never a satisfactory explanation.

Morfydd Clark, utterly brilliant in Roots, feels slightly miscast as Alison’s aristocratic friend Helena who takes the former’s place in Jimmy’s affections. “Viry will, I’m liffing” she tells Jimmy at one point with the kind of strangulated posh-totty vowels one associates with Brief Encounter. Davies’ top-notch, restrained Cliff loves Jimmy every bit as much as the others do. Even Alison’s dad (Deka Walmsley on great form) reveals an affinity for the man.

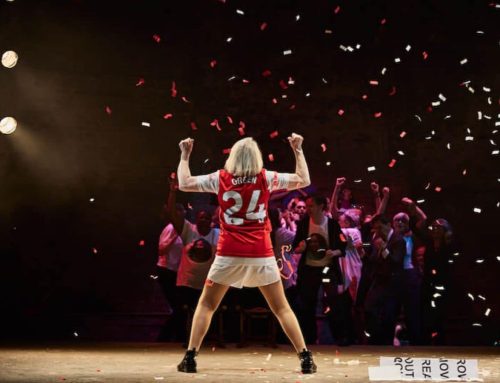

Does Look Back In Anger reverberate in 2024? In the scenes of homoerotic playfighting with Cliff one gets the feeling this Jimmy would be quite as open to sexual experimentation as any Gen Zer, and the idea that three people share a flat because they cannot afford to live separately feels familiar enough. Banerjee’s paired back, understated production, laden with symbolism, emerges as cathartic if not exactly enjoyable. He gives us dreamy, haunting offstage jazz riffs to denote the feel and tone of the 50s. The final scene sees a rain of ash fall from above and build around Alison, literally encasing her in the mud and filth that is Jimmy’s world.

Naomi Dawson’s set, a red circular dais, edged in white and tiered like a wedding cake, revolves gently. In Roots the revolutions speed up or stop completely to highlight narrative points. Here the centre opens up to make space for fleeting dance pieces that reveal the angst in the duo’s relationship. The symbolism is impressive but sits a little at odds with the studied naturalism that Osborne normally evokes. A solid production and the masterpiece still shocks.

Writer: John Osborne

Director: Atri Banerjee

More Recent Reviews

Playfight. Soho Theatre.

Writer Julia Grogan’s breathtakingly assured debut play arrives at Soho Theatre following stellar reviews at the Edinburgh Fringe and [...]

All The Happy Things. Soho Theatre.

Naomi Denny’s three-hander comedy-drama All The Happy Things covers familiar themes within a recognisable premise. A grieving protagonist comes [...]

Telly. Bread and Roses Theatre.

The challenge with absurdist comedy is that many people do not find it funny. Laughing at the sheer weirdness [...]