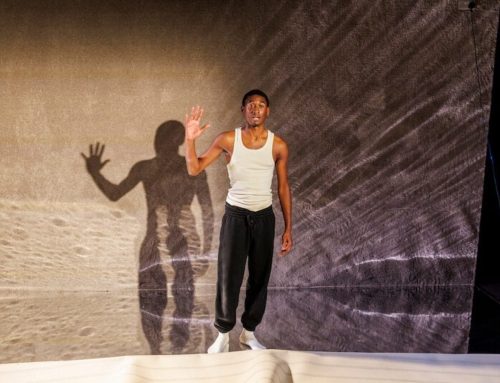

The Bush Theatre has a rich history of programming new works by British Black and Asian writers, including a recent hit West End transfer with Benedict Lombe’s bittersweet rom-com Shifters. Bush Young Company alumnus Azan Ahmed’s Statues, with its fusion of gentle comedy and hard-edged political message, offers an immensely likeable addition to the tradition.

Oxford-educated Yusuf (writer Ahmed is a fine actor too) is a small-c conservative British Asian English teacher with an Ofsted epithet as “modern, approachable, and compassionate”. He has two weeks to clear out his sullen late father’s council flat in Kilburn. A work promotion and a difficult year-13 pupil named Khalil (an engaging Jonny Khan) add to the strain, leaving him feeling lightheaded and “rigid like stone,” though he divulges “that might just be last night’s kebab”.

By chance, Yusuf finds a cassette tape from Dad’s youth featuring Bangla-inspired, hip-hop tunes about Kilburn, love, and being Muslim, Asian and British. “My Babba was a rapper… a cool MC,” says the astonished schoolteacher. So, what happened to turn that cheeky, “badmaash”, charmer of the 90s into such a grim, reticent old man? Babba “was hard work” we hear, so something bad must have transpired. Yusuf’s class is studying Hamlet. Like the Prince of Denmark, Yusuf embarks on a journey to uncover the truth about an absent father.

Ahmed does not directly interrogate how or why Yusuf’s relationship with his Dad becomes so distant, which is a shame because there are hints of intergenerational cultural conflict here. Instead, his focus is on what he perceives as three generations of British Asian self-censorship in the face of racism and false allegations of radicalisation.

“I’m stuck without being able to say what I think,” the teacher tells us: a statue frozen in a verbal prison partly of his own making. The sentence hints at Dad’s dilemma in the 90s and 17-year-old Khalil’s challenge in the present day too. The pupil sees Hamlet as a radical fighting for truth and justice in the face of oppression. But if even using the words “radical” and “oppression” at school invites unwanted police attention, what choice is there but to shut down the discussion and fit into white cultural expectations?

Esme Allman’s pacey direction smooths the narrative time shifts between Babba’s era and the present day. As a way of moving forward, Yusuf advises Khalil to “pick a word you want to untangle from” and explore it. Dad does this in an affecting and beautifully executed alliterative rap that reclaims the P-word as a source of pride.

Writer: Azan Ahmed

Director: Esme Allman

More Recent Reviews

The King of Hollywood. White Bear Theatre.

Douglas Fairbanks was a groundbreaking figure in early American cinema. Celebrated for his larger-than-life screen presence and athletic prowess, [...]

Gay Pride and No Prejudice. Union Theatre

Queer-inspired reimaginations of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice are a more common species than one might initially imagine. Hollywood [...]

Knife on the Table. Cockpit Theatre.

Knife on the Table, Jonathan Brown’s sober ensemble piece about power struggles, knife violence, and relationships in and around [...]