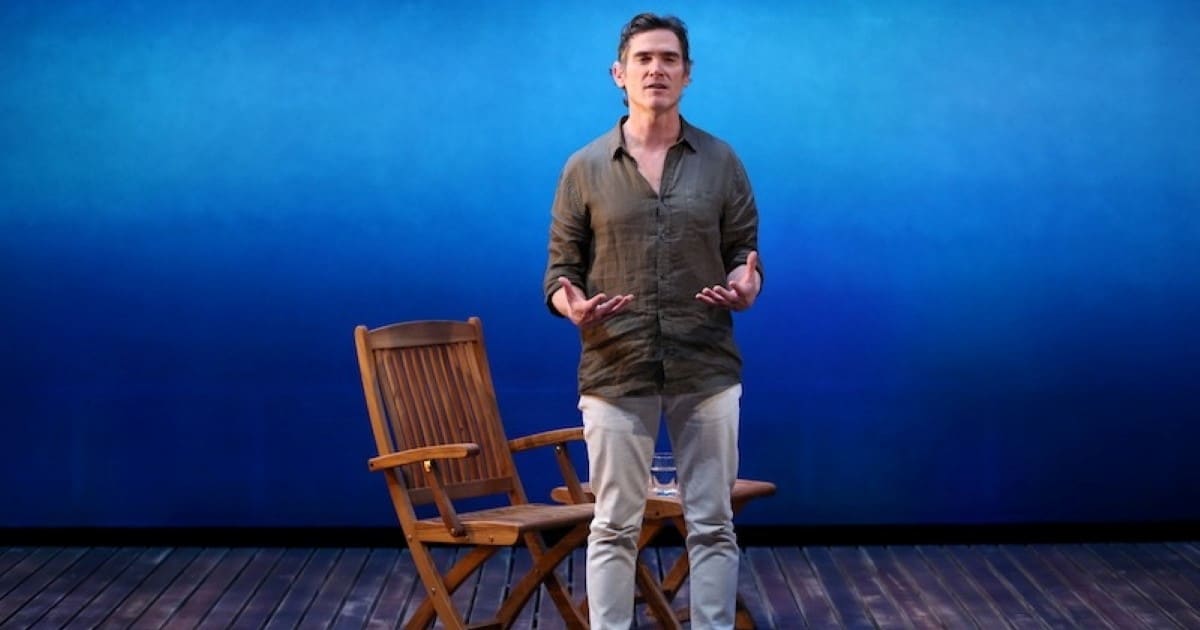

David Cale’s deliciously malign noirish comedy Harry Clarke, with an absolutely stunning turn by Billy Crudup as the eponymous Harry, was first seen in an award-winning extended off-Broadway production back in 2017. The Ambassadors Theatre’s welcome and overdue London outing is an utter delight. Crudup’s unmissable performance is a masterclass in the art of delivering monologue. His venal, manipulative, sexually voracious Harry offers up one of those rare creatures in theatre: a character that feels fully formed, wholly novel, and instantly recognisable. “I’m Harry Clarke and I’m gonna mess you up,” he tells us early on, and he means it.

Philip Brugglestein is a fey, camp, sociopathic dreamer from rural Indiana who discovers at the age of eight that he can speak with a cod English accent. “It’s my real voice… I can be myself”, he tells us. The “Britty Brit” affectation drives his brutal, alcoholic father to distraction, which one suspects is why Philip does it. Cancer kills his mum and something more sinister kills his dad (we learn what late on) leaving Philip alone in New York City at the age of 18.

Surviving on occasional barista jobs and a dwindling inheritance, Philip passes the days watching ‘50s Hollywood crime dramas and experimenting with a cocky, cockney alter-ego called Harry Clarke. Rather like a novelist with a new character to play with, Philip is trying Harry on for size with an eye to letting him loose and seeing what he gets up to. Sexually ambivalent, bubbling with manic self-confidence, and with an accent culled from British films, Harry can do the things Philip cannot.

A chance street encounter sees Philip stalk wealthy, handsome Connecticut jock Mark Schmidt, who is buying underpants in a Gap store while rowing with his girlfriend. “Now I know what it’s like to follow someone around” he confesses with barely concealed delight. In some senses Philip and Mark are warped mirror images of each other. Both traumatised by deeply homophobic fathers, Mark flees into drink and drugs while Philip escapes into Harry.

Plot machinations see the duo meet at a theatre. But it is alter-ego Harry Clarke, now claiming to be singer Sade’s personal assistant, who introduces himself. Clarke inveigles himself into the serious money world of the Schmidt family, where his English charms seduce not only Mark (“That was the deep end of sexy” he says after enticing a drunken Mark to bed), but also song-writing sister Stefanie. Even big-haired mum Ruth, who justifies her aversion to oral sex with an uncircumcised man by explaining she “can’t eat shrimp either”, gets a look in. The trickster’s efforts to maintain his carefully constructed fantasy identity soon face challenges. The line between Philip and his creation blurs and the risks become bigger. “I’ve got on a ride, and I can’t get off it”, he confesses.

There are hints of Alan Bennett’s Talking Heads in the monologue’s acerbic humour and carefully camouflaged revelations. But unlike many of Bennett’s inventions, one suspects Harry is a more or less truthful narrator. With Clarke, what you see is what you get. There are hints of Saltburn and Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr Ripley here too. But unlike in those productions, Harry’s actions, grotesque and warped as they often are, are largely driven by something approximating to what he thinks is kindness. At one point he practices in the mirror over several iterations the most convincing way he can devise of confessing his love for Mark. Serpentine scheming yes, but deep down the feelings are genuine enough.

Crudup’s sly, devious, brutally funny Harry is an intoxicating revelation. The joke, at least for an English audience, is that Harry’s faux south London blaccent is dire. Imagine the demonic offspring of a union between Michael Caine, Cary Grant, Ali G, and spoof spy hero Austin Powers, conceived on the set of a Guy Ritchie film, and you will get some sense of the way he talks. The character’s swaggering, ambling pimp role, constantly jabbing hand gestures, and ogling eye contact scream cultural appropriation, although Harry would not know what cultural appropriation is if it hit in the face with a rolled up copy of British GQ. Ultimately Crudup’s Harry is inscrutable, his sexual identity as uncertain and inconstant as the rest of him.

Cale, who grew up in the UK and now lives in the US, marks his British debut as a playwright with Harry Clarke. One hopes we will see much more from him.

Writer: David Cale

Director: Leigh Silverman

More Recent Reviews

The King of Hollywood. White Bear Theatre.

Douglas Fairbanks was a groundbreaking figure in early American cinema. Celebrated for his larger-than-life screen presence and athletic prowess, [...]

Gay Pride and No Prejudice. Union Theatre

Queer-inspired reimaginations of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice are a more common species than one might initially imagine. Hollywood [...]

Knife on the Table. Cockpit Theatre.

Knife on the Table, Jonathan Brown’s sober ensemble piece about power struggles, knife violence, and relationships in and around [...]