There are tangibles and intangibles in Zoe Cooper’s enjoyable adaptation of prominent young adult writer David Almond’s mystical and dreamlike coming of age novel A Song For Ella Grey. Directed at almost breakneck pace by Esther Richardson, the production occasionally struggles to reconcile the narrative’s more abstract elements of Greek-myth with the demands of a theatrical milieu. But tremendous performances from a cast drawn from the North East, Emily Levy’s enchanting Newcastle-inspired folk music palette, and Verity Quinn’s stripped back impressionistic set design offer up enough to paper over most of the cracks.

On the tangible side are the five likeable young characters. Friends from primary school and now preparing for A levels with the cranky but caring teacher they label ‘Krakatoa’, they exist in that enigmatic liminal space between childhood and adulthood. This is a place where feelings around friendship, love, and sexual desire are as powerful and plastic as they are ever likely to be. The quintet know chunks of John Dunne love poems and Romeo and Juliet off by heart and interact with each in an ever-evolving whirlwind of emotionally loaded links that one of them labels “this continent of us”. As one of the songs has it, this is a group “standing on the edge of belonging”.

Arty Claire (a passionate, engaging, and accessible performance from Olivia Onyehara), encouraged by wine-swilling uber-liberal academic parents, thinks she “doesn’t need a constellation of A-stars to be a poet”. One suspects she may have to rethink that one later on. Claire is secretly in love with ethereal Ella (a strikingly restrained Grace Long), who lives in “a pin-smart three-bed semi” with “immaculate DFS sofas” and a mum who is even more rigid than her stickler of a dad. Then there is thoughtful geography-lover Jay (Jonathan Iceton), who is perhaps neurodivergent and knows the rocks and wildlife of the North East like the back of his hand. Add into the mix quirky Angeline (Beth Crame who shines in a number of other cameo roles) and academically challenged Sam (a charismatic Amonik Melaco) who has a thing for Claire every bit as strong as Claire’s passion for Ella.

Here things become rather more elusive and symbolic. The five begin to hear a strange, disembodied, otherworldly ballad. Like a banging summer Ibiza anthem cum siren-song, the kids just cannot get the tune out of their brains. Things come to a head on first day of February half-term when four of the five (Ella’s suspicious parents ground her) take advantage of the “shadowy beauty of a Northumberland spring” to head off to Bamburgh Beach for some impromptu camping, stargazing, and Tesco Valpolicella. Orpheus, here presented in silhouette form as a kind of Jesus Chris-like figure, complete with a gothic-horror crown of twigs in the place of thorns, appears to captivate the group with the melodious sound of lyre.

Each one develops a distinct connection with Orpheus, assigning the character a gender identity based on their own desires and needs. But it is Ella (the story’s Eurydice), connecting to the beach over a crackling phone line, who falls in love. She has “a secret smile she shares with Orpheus alone”. Orpheus asks Ella to marry, but really it is the girl in the driving seat here. Almond’s feminist reworking of the myth assigns Ella the agency which the mythical Eurydice manifestly lacks.

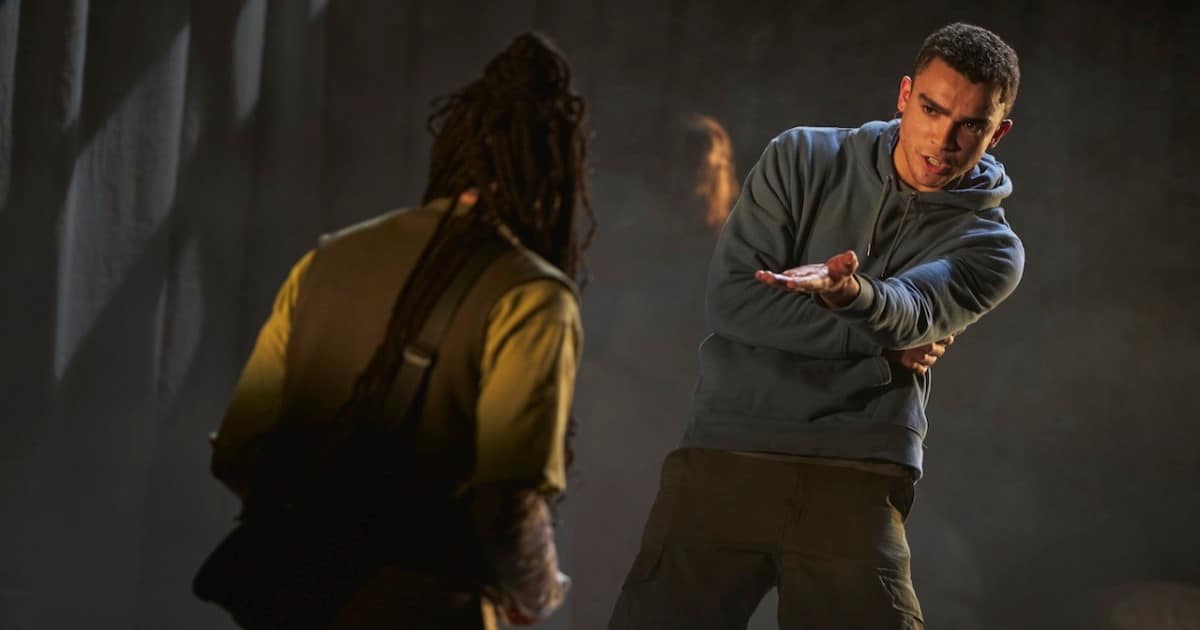

Tragedy strikes when Ella is bitten by a snake and dies. A heart-broken Orpheus (played jointly by each of the other four characters) follows her to the underworld to bring her back. Is it a hopeless task? Like the uncertain and bumpy passage from adolescence to adulthood, is death inevitable? “All of the voices of all of the people that ever loved Ella Grey” must come together to try to call her home. “Pull me back to the future of us” sings Ella as the quest unfolds. “Can you be both young and dead?” says Claire. Anyone who has ever read the Greek original will know the answer to that. Anticipate tears.

Cooper’s story, told in retrospect through a combination of narration and dialogue, zips along, foregrounding the themes of teen romance, loss, and coming to terms with grief. The queer central love story is refreshingly direct, but who or what Orpheus actually represents remains frustratingly out of reach.

Levy draws on folk tunes to evoke the North East coast, with a rendition of When The Boat Comes In and The Magpie Song proving both inspiration and atmosphere. Her underworld soundscape is a thudding, forbidding dance beat. Quinn’s set, white curtains, duvets and banked white mattresses for Newcastle, forbidding black islands for the underworld, is finely rendered. Back projections of churning clouds, turbulent seas and swirling flocks of birds add tone without being too obviously naturalistic.

Writer: David Almond (adapted for the stage by Zoe Cooper)

Director: Esther Richardson

More Recent Reviews

The King of Hollywood. White Bear Theatre.

Douglas Fairbanks was a groundbreaking figure in early American cinema. Celebrated for his larger-than-life screen presence and athletic prowess, [...]

Gay Pride and No Prejudice. Union Theatre

Queer-inspired reimaginations of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice are a more common species than one might initially imagine. Hollywood [...]

Knife on the Table. Cockpit Theatre.

Knife on the Table, Jonathan Brown’s sober ensemble piece about power struggles, knife violence, and relationships in and around [...]