It is Groundhog Day at the Old Vic. No, not yet another revival of A Christmas Carol – that delight comes later this year – but an amiable, if a tad soulless reworking of the theatre’s 2016 titular musical hit, with book by Danny Rubin and music and lyrics from Tim Minchin. Andy Karl reprises his Olivier award-winning role as profoundly narcissistic TV weatherman Phil Connors, whose almost Shakespearean journey of self-reinvention provides the driving, indeed almost only, narrative force of the show.

The loathsome Connors reluctantly finds himself on an annual February reporting trip to Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, there to cover the appearance of a local weather-predicting groundhog. If the creature emerges and sees its shadow, it is a sure sign that the hick town will suffer another six weeks of winter. Connor wholly fails to predict a “blizzard donut” that traps the TV crew in town for the day. When he wakes the following morning, desperate for the kind of decent coffee that a grim small-town bed and breakfast just cannot provide, he finds himself trapped in a time loop in which he is destined to relive the same day again and again. But will this endless repetition of 24 hours in a cynical man’s meaningless life be a gift, or a burden, and just how will he achieve the redemption he so desperately requires?

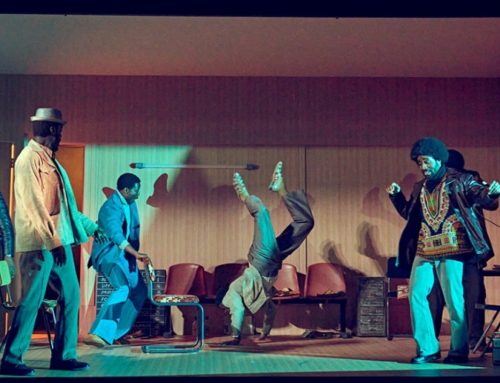

Andy Karl brings a kind of oleaginous sexual braggartry to his Connor, whose initial euphoria at total freedom from responsibility is marked by sleeping with the entire female population of the town, plus “a few dudes” when he gets bored. The one woman he cannot bed, try as he might, is his producer Rita (a sparky and charismatic Tanisha Spring). Connor’s honeymoon of hedonism soon palls, giving way to a dark realisation that without something to live for tomorrow, today lacks purpose. The show’s best comic moments come in some cleverly executed theatrical tricks that see the character killing himself on one part of the stage, only to reappear full of life on another.

So entirely concerned with Connors is the show that the other characters are here primarily as love object or foil. Spring’s Rita gets to sing to her diary about how she lacks opportunities in a world of men. It is an apt song, because really her role here is as an agent in Connor’s redemptive journey, rather than a protagonist in her own right. Without any subplot to speak of this leaves Rita without an awful lot to do. Nancy (Eve Norris), one of Connor’s early sexual conquests, has one of the show’s best tunes in Playing Nancy. It is a winsome ballad about the performative nature of a someone playing the role of a blond bimbo, one that she falls into because it is easy and expected of her. She is trapped in her unwanted role every bit as much as Connors is trapped in his, but it is really only the male character who gets to change here.

Mid-way through the second half, Connors comes to a realisation that he is a kind of Punxsutawney god: an all-seeing, omnipotent force of nature who has the power to bring good into the townspeople’s lives. The showstopper and Groundhog Day’s best number, Hope, is a brilliantly executed ensemble piece about the power of self-acceptance and the pleasure to be found in just being nice to people.

Tim Minchin’s musical palette ranges from twangy country to generic soft rock, through to folksy choral numbers. It is a range that feels a little frantic at times, particularly in the first half. The tunes are catchy, but not always particularly memorable and you are unlikely to be humming anything on the way out. There is plenty of wit though in the lyrics. In his desperate early attempts at finding a medical explanation for his apparent madness Phil undergoes medical tests; “Who needs enemas with friends like this?” he asks.

Rob Howell’s set, a backdrop of miniature houses, onto which a revolving selection of bar, diner, and a dingy bedroom transition, cleverly evokes the small-town feel. If nothing else, you will leave this show wanting to see the original 1993 film again. Andy Karl’s version of Connors is a lots more poisonous than even Bill Murray’s misanthrope, which perhaps suits these more caustic, fractious times better.

Book: Danny Rubin

Music and Lyrics: Tim Minchin

Director: Matthew Warchus

More Recent Reviews

Playfight. Soho Theatre.

Writer Julia Grogan’s breathtakingly assured debut play arrives at Soho Theatre following stellar reviews at the Edinburgh Fringe and [...]

All The Happy Things. Soho Theatre.

Naomi Denny’s three-hander comedy-drama All The Happy Things covers familiar themes within a recognisable premise. A grieving protagonist comes [...]

Telly. Bread and Roses Theatre.

The challenge with absurdist comedy is that many people do not find it funny. Laughing at the sheer weirdness [...]