England, 1640. The nation, awash with paranoia over the apparent presence of devilry and witchcraft in every corner, stands on the brink of a brutal civil war. Lady Elizabeth (the always watchable Lydia Leonard) has more matter-of-fact troubles on her mind. Her bumptious, beef-loving, buffoon of a brother, local lord of the manor Edward (Leo Bill) has failed to sire an heir for the family estate. Elizabeth, determined to protect her ancestral home from the hands of scheming cousins, sets about finding her sibling a suitable wife. She has her eye on Katherine (Ionna Kimbrook) whose family background is in trade and who knows nothing of the birds and the bees. Thankfully, the tradesman’s daughter has a ton of money.

There is a hitch. Edward’s sexual interests lie mainly in impregnating the staff below stairs, and indeed in the voluptuous delights of his own sister. In addition, in dim, hard-drinking, and highly forgetful Edward’s way of thinking, the real betrayal of his family heritage resides not in losing the house but in marrying a girl of the wrong class. He make take some persuading that the virtuous and humble Katherine is worthy of his attentions.

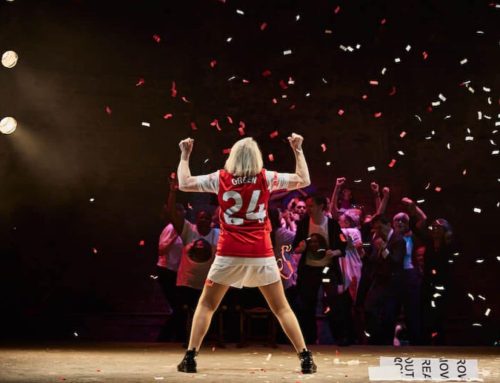

Enter ambitious, quick-witted local farm girl Agnes (Alison Oliver, whose journey from naïve innocent to competent trickster is the highlight of the evening). Her mother was a witch, and, despite vocal protestations to the contrary she has something of her own reputation in the black arts. Elizabeth has a proposal for the farm girl – use your magic to convince a reluctant Edward to marry, or I will see that you hang. Agnes, who not so deep down wants to read books, eat off fine plates, and wear silk like the posh people, has a tough choice to make. The Devil (a horned, black-clad, feline fingernailed and enjoyably malign Nathan Laryea) is on-hand to help out in a variety of different guises. Anticipate double-crosses, twists, turns, blood, and gore aplenty, all set at the outset of a period of epoch-making national change. “Come with me” Agnes says at various points to the characters who stand in her way. When they refuse, they become part of the problem. As with the burgeoning civil war, it is possible there may only ever be one winner here.

It is not altogether clear what writer Raczka and director Rupert Goold are aiming at in Women, Beware the Devil, or indeed what we are meant to make of Agnes. The rural setting, isolation, and topics of superstition, paganism, and blood sacrifice suggest folk horror, but the show is too mannered to invoke any kind of fear or foreboding. There are some broad laughs and Leo Bill in particular has great comic timing. But gags are few and far between, and with the exception of a witty running joke about the absence of beef from the table (seemingly a result of Agnes’s diabolic handiwork) the comedy often feels laboured.

Perhaps Raczka sees Agnes as a catalyst for the revolutionary change that forms the show’s narrative backdrop: the tearing down of the Royalist power structures and their replacement by Cromwell’s puritanism. If so, the contemporary historical connections are woefully under-explored. There are some fourth wall breaking interludes that invite the audience to compare past events to those of the present day. Agnes as a metaphor for the Brexit voting, abandoned northern working class? She is certainly an agent for chaotic change in a house that feels dark, depressed, and decayed, and in urgent need of revolutionary transformation. A prologue from the devil himself tells us that in these days of strikes, inflation, and war we no longer require his presence, so perhaps the piece is a primarily meant as a comment on our modern state. It is all maddening vague and Raczka seems in no particular hurry to make intentions clear.

Equally ambiguous is the presence of the devil, who reappears variously as a physician, fey artist, aggressive witchfinder, Cavalier general and Roundhead foot-soldier. Is he an agent of justice enabling an unassuming farm girl to achieve some kind of social fairness, or a reactionary figure, determined to ensure that however much the military uniforms change, real power stays in the same place? Perhaps he is both and neither.

Writer: Lulu Raczka

Director: Rupert Goold

Miriam Buether’s set design is spectacular: a checkerboard drawing-room, with pitch black wooden panelling, hidden doors, and a four-poster bed that rises from beneath the floor. It has the perspective brilliance of Leonardo’s Last Supper. The gorgeous dinner scenes, with the table dripping in blood red fruit could come straight out of a High Renaissance painting.

Women, Beware the Devil has sparky moments. If only it would make its intentions a little clearer.

More Recent Reviews

The King of Hollywood. White Bear Theatre.

Douglas Fairbanks was a groundbreaking figure in early American cinema. Celebrated for his larger-than-life screen presence and athletic prowess, [...]

Gay Pride and No Prejudice. Union Theatre

Queer-inspired reimaginations of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice are a more common species than one might initially imagine. Hollywood [...]

Knife on the Table. Cockpit Theatre.

Knife on the Table, Jonathan Brown’s sober ensemble piece about power struggles, knife violence, and relationships in and around [...]